Ever since the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit decided Zeig v. Mass. Bonding & Insurance Co. in 1928, it has been well-settled that a policyholder can compromise a disputed claim with its insurer for less than the full limits of the policy without putting its rights to excess coverage at risk. In a seminal opinion by Judge Augustus Hand, the Zeig court said, “We can see no reason for a construction so burdensome to the  insured,” to require collection of the full amount of primary polices in order to exhaust them. The Zeig court emphasized that a compromise payment by the primary insurer discharges the limits of the primary coverage, while the excess insurer is unharmed, since it must pay only the amount exceeding the attachment point of its policy.

insured,” to require collection of the full amount of primary polices in order to exhaust them. The Zeig court emphasized that a compromise payment by the primary insurer discharges the limits of the primary coverage, while the excess insurer is unharmed, since it must pay only the amount exceeding the attachment point of its policy.

While some recent decisions have made policy-specific exceptions to that rule, a June 7 opinion of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court of the Southern District of New York in Rapid-American Corp. v. Travelers Casualty & Surety Co. calls the rule itself into question. Accrued but unpaid liabilities that exceed primary coverage limits may no longer trigger excess coverage. In Judge Bernstein’s recent opinion, the primary insurer may have to pay its full limits before excess coverage is available.

Rapid-American was saddled with numerous asbestos-related personal injury claims and reached below policy limit settlements with several of its primary and excess insurers before later filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Rapid-American brought suit against certain of its excess insurers who denied coverage on the basis that primary coverage was not yet exhausted. Rapid-American moved for summary judgment claiming that the primary policies had been exhausted, and the excess insurers breached their respective contracts by denying coverage. The court assumed for purposes of the motion that the company had accrued liabilities that reached its excess coverage layer. It was undisputed however, “that neither Rapid nor anyone else ha[d] actually paid through settlement, judgment or otherwise an amount sufficient to reach the level of excess coverage provided under the policies at issue.”

Relying on Zeig, Rapid-American argued that its primary policies were exhausted when it settled with and released the primary insurers, even when they had not paid their full policy limits in cash. The bankruptcy court disagreed and questioned the continuing vitality of Zeig. Judge Bernstein held that an actual payment of the full primary policy limits must be made by someone before excess coverage is triggered. The court reasoned that a contrary holding might tempt policyholders to manipulate settlements in order to reach higher levels of excess coverage.

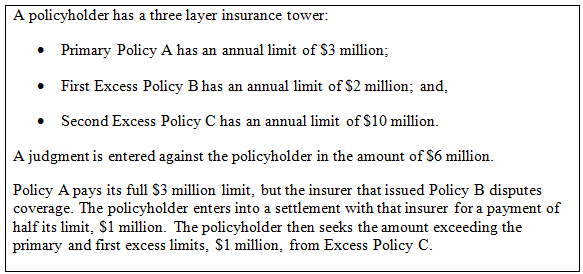

Consider the following hypothetical.

Under Judge Bernstein’s decision, Excess Policy C cannot be triggered—even though the losses reach its coverage—because Excess Policy B’s full limits were not actually paid. The fact that a judgment was entered that exceeded the policyholder’s $5 million in primary and first-layer excess coverage is of no consequence. Because only $4 million has been paid, excess coverage may not be triggered. Under the prevailing rule in Zeig, however, the policyholder would be entitled to claim coverage under Excess Policy C.

While specific policy language has morphed over time, and factual circumstances are often case-specific, important policy considerations nevertheless favor continued application of Zeig. As Judge Hand wrote in 1928, “To require an absolute collection of the primary insurance to its full limit would in many, if not most, cases involve delay, promote litigation, and prevent an adjustment of disputes which is both convenient and commendable. A result harmful to the insured, and of no rational advantage to the insurer, ought only to be reached when the terms of the contract demand it.” Judge Bernstein’s holding makes it much more difficult to settle insurance cases.

The good news is that Rapid-American is a bankruptcy court opinion, and cannot overrule circuit precedent. Moreover, Rapid-American hinges on a dubious reading of several recent precedents, construing decisions that distinguished Zeig as if they had questioned its reasoning. Nonetheless, Rapid-American presents a cautionary tale for policyholders. Review your excess policy language when settling with primary insurers—and make sure you’re not giving up more than you bargained for!

Policyholder Pulse

Policyholder Pulse