In August, we provided an overview of the recent increase in regulatory and private litigation activity around per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), colloquially known as “forever chemicals,” and potential insurance coverage for PFAS liability. There have been important developments on the PFAS front in the past few months. Companies with any connection to PFAS need to be cognizant of the evolving regulatory landscape and be prepared to defend against potential PFAS liability. Fortunately, insurance coverage may be available to help mitigate these fast-growing claims—including coverage under historic general liability policies.

In August, we provided an overview of the recent increase in regulatory and private litigation activity around per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), colloquially known as “forever chemicals,” and potential insurance coverage for PFAS liability. There have been important developments on the PFAS front in the past few months. Companies with any connection to PFAS need to be cognizant of the evolving regulatory landscape and be prepared to defend against potential PFAS liability. Fortunately, insurance coverage may be available to help mitigate these fast-growing claims—including coverage under historic general liability policies.

PFAS Regulatory Developments

Federal and state legislatures and regulatory bodies are endeavoring to address PFAS usage and contamination. On the federal legislative front, in July 2021, the U.S. House of Representatives approved H.R. 2467, which would require the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to include PFAS on the list of hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA, or “Superfund”), triggering federally-mandated cleanup requirements. Additionally, H.R. 2467 designates PFAS as “toxic pollutants” under the Clean Water Act. A separate bill, recently introduced in the U.S. Senate, also would prohibit PFAS in food packaging and wrappers. If passed, the federal government would join seven states—California, Connecticut, Maine, Minnesota, New York, Vermont, and Washington—that have passed laws banning PFAS in food packaging. These are just a few of some three dozen PFAS-related bills currently pending in Congress.

On the regulatory front, in October 2021 the EPA outlined its PFAS Strategic Roadmap. This document, which is summarized here, calls for a “whole-of-agency” approach to regulating PFAS. The Roadmap accelerates the timetable for implementing PFAS-related actions under multiple environmental statutes over the next three years. The Roadmap stands to (i) expand the scope of PFAS subject to federal regulation, (ii) impose reporting obligations on companies that produce, process, and otherwise use PFAS, and (iii) advance the codification of regulatory criteria for addressing the release of certain PFAS in the environment. If implemented, the Roadmap would introduce sweeping regulations and create additional liabilities, both for active PFAS users/manufacturers and for companies that have legacy liabilities related to PFAS.

Shortly afterwards, on October 26, 2021, the EPA proposed two rulemakings to facilitate the remediation of PFAS contamination under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). One rulemaking proposed to list four PFAS chemicals as “hazardous constituents”— the necessary first step towards subsequently designating them as a “hazardous waste,” which would bring these chemicals within the full ambit of RCRA regulation. Moreover, even without a subsequent “hazardous waste” designation, this rulemaking may subject PFAS to RCRA’s onerous corrective action requirements. The second proposed rulemaking clarifies a longstanding discrepancy between RCRA and its implementing regulations to assert a broader scope of contamination subject to RCRA corrective action than advocated by industry in the past.

Approximately three weeks later, on November 16, 2021, the EPA submitted to its Science Advisory Board documents regarding the adverse health effects of certain types of PFAS substances. Those documents show that negative health effects from certain PFAS may occur at much lower levels of exposure than previously understood; they also identify one type of PFAS as a likely carcinogen. As a result, some anticipate that the EPA may set a very low threshold for PFAS exposure, well below the regulatory criteria for other harmful chemicals such as volatile organic compounds. This could serve as an impetus for increased liability and remediation costs.

At the state level, there has also been an uptick in PFAS-related enforcement and cost recovery actions, especially in jurisdictions with PFAS drinking water standards in place. In addition, a number of states have begun to draft legislation to identify and eliminate PFAS usage. For example, on November 30, 2021, the Florida State Senate approved Senate Bill 7012, which mandates the examination of alternatives by which the state can eliminate PFAS and related chemicals in state commerce. The bill also would create a PFAS Task Force within Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection, which would be charged with developing recommendations on enforceable regulatory standards for PFAS in drinking water, groundwater, and soil, including sampling and monitoring requirements, mechanisms for identifying and addressing PFAS contamination and funding its cleanup and treatment; methods of waste managements and mitigation of releases from disposed or discarded products; and methods to eliminate workplace exposure in the manufacturing industry.

The increased scrutiny on PFAS should serve as a call to action for corporations with potential exposure, as legislative and regulatory activity will lead to a significant increase in regulation, remediation obligations, and potential enforcement actions and private lawsuits.

PFAS Litigation Developments

Meanwhile, substantial litigation continues against PFAS manufacturers, especially those that allegedly contributed to groundwater contamination. For example, last month, DuPont, 3M, Chemours, Corteva, and others were sued in South Carolina federal court by California’s largest groundwater agency, claiming that the companies polluted Los Angeles County’s drinking water. That suit alleges, among other things, that the manufacturers “knew or should have known that their PFAS compounds would reach groundwater, pollute drinking water supplies, render drinking water unusable and unsafe, and threaten the public health and welfare.”

Although the litigation trend to date has been to sue PFAS manufacturers, many other companies may face legal exposure. Consider a notable recent ruling by a Georgia federal court in Johnson v. 3M Co., a proposed class action involving homeowners who alleged their drinking water supplies had been contaminated by PFAS that had been released into the environment from treated textiles. On September 20, 2021, the court dismissed negligence claims against the primary manufacturers of the PFAS products used to treat the textiles, while allowing claims to proceed against water utilities and carpet manufacturers for their alleged role in releasing PFAS into the environment. The federal court’s ruling stands to shift the burden of PFAS-related liabilities from the relatively smaller circle of primary manufacturers onto the broader group of secondary manufacturers and downstream processors.

Moreover, even settled PFAS claims can prove to be quite expensive. For example, in October 2021, 3M agreed to pay approximately $98 million to settle with environmental group Tennessee Riverkeeper and a separate class-action consisting of local residents and the city of Decatur, Ala. (where a 3M plant is located), for claims that 3M contaminated the Tennessee River with toxic chemicals.

PFAS Insurance Considerations

As discussed in our last post, companies facing PFAS liability should explore whether their pre-1986 general liability policies may provide coverage. General liability policies may cover liability arising from property damage or bodily injury if the damage or occurrence that caused it took place during the policy period, regardless of when liability is imposed. Thus, liability arising today—whether by statute, regulation, enforcement action, lawsuit, or other demand—could be covered under pre-1986 policies. Given that PFAS have been widely used in numerous applications for many decades, PFAS contamination commonly will go back in time and implicate those historic policies.

That said, the availability of coverage under pre-1986 policies will depend on whether a qualified pollution exclusion (also known as the “sudden and accidental” pollution exclusion) bars coverage. This requires careful analysis of the policies themselves, the facts relating to the policyholder’s PFAS liability, and potentially governing law. Importantly, many pre-1986 policies issued to corporate policyholders do not contain the qualified pollution exclusion. As for policies that do, a critical question is what state’s law governs the interpretation of the policy, as some states’ courts have ruled that the exclusion does not apply if the contamination was unexpected, while some other states’ courts have ruled that the exclusion applies unless the discharge is both unexpected and temporally abrupt. The choice of law question rarely is straightforward, as pre-1986 liability policies typically did not contain a governing law provision and states have varying choice of law rules. And, whether the specific facts and circumstances involved fit within the pollution exclusion or its exception also requires careful analysis and a good understanding of the nature of the alleged PFAS injury or damage.

Another issue to consider regarding pre-1986 policies is whether rights under those policies were released in a prior settlement. Over the past 35 years, many large U.S. companies have made significant claims under their pre-1986 policies with respect to liability for asbestos bodily injury claims, environmental contamination, or otherwise. Those large claims sometimes resulted in broad settlements in which some or all rights under pre-1986 policies were released. Any such settlement agreements need to be reviewed closely to determine whether coverage remains in place for PFAS liability.

Companies facing PFAS liability also should consider whether any of their current or recent environmental-specific insurance policies provide coverage. Present-day environmental policies vary widely. These policies often provide coverage for environmental regulatory actions and orders and private third-party environmental claims. Such policies may have limitations regarding how long ago the contamination commenced, when the contamination was discovered, when it was reported to the insurer, and the like. Coverage also may be site-specific rather than generally applicable to the company’s operations. Present-day environmental policies also may contain a PFAS exclusion or other potentially applicable exclusions. Once again, a careful review of such policies is necessary to assess potential coverage.

Final Thoughts

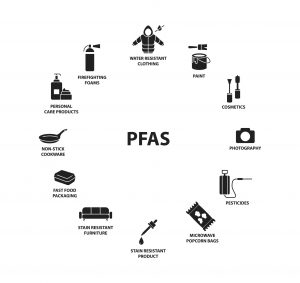

PFAS liability via statute and regulation, government enforcement, and private lawsuits poses a significant threat to both PFAS manufacturers and other companies that have “touched” PFAS in some way. PFAS are used in a wide array of products, including firefighting foam, Teflon, shoes, carpets, clothing, and many others. PFAS chemicals travel quickly and can continue to persist in groundwater and the human body. Companies with potential PFAS liability should review their current and historic liability insurance policies. After all, as their name indicates, forever chemicals, unfortunately, are here to stay.

RELATED ARTICLES

PFAS Enforcement and Liability Is on the Rise—Insurance Can Help

Is Your Insurance Program Ready for the Biden Administration?

Policyholder Pulse

Policyholder Pulse